THE FACTORY GIRLS

By Frank McGuinness

Directed by Nye Heron

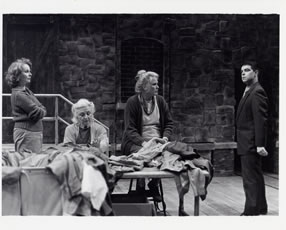

Frank McGuinness has enjoyed a multi-faceted career in the theater. Except for Someone Who'll Watch Over Me which in 1993 won the New York Critics' Circle Award for Best Foreign Play he's best known to American audiences for his ground breaking adaptations of A Doll's House (a quadruple 1997 Tony Award Winner) and Electra (a 1999 Tony nominee) and the movie version of Dancing at Lughnasa). With the exception of the Macalla Theatre in the Bronx which dedicated to bringing contemporary Irish theater to its surrounding Irish community, no one in this country has ever produced this funny yet ultimately sad early 80s slice of five working women's lives. The Williamstown Theatre Festival is to be commended for giving us a chance to see the play that launched McGuinness's career and doing so with this beautifully staged production.Since The Factory Girls is more character than plot driven, it requires actors up to the job of delineating each of the women as more than just a type. While the playwright does better by some characters than others, the actors all do well -- better than well, in fact -- by their parts. The monotonous work they do -- the end of the line process of making sure all buttons and pockets are in place -- symbolizes the overall end of the line situation that escalated the redundancy of many factories and their employees from the 1960s onward. It is this play's factory's struggle to survive against he competition of cheaper labor in other parts of the world that catapults Ellen (Celia West on), Vera (Kate Burton), Rebecca (Bernardine Quigley), Una (Rebecca Schull) and their young messenger Rosemary (Groschen Cleverly) from their uneventful lives into a desperate sit-in strike in the whimpy new manager's office (Christopher McHale).

Things move along at a quiet, leisurely pace. While there's constant interaction, there's very little action. This gives these proceedings much the same sense of listening in on the women that audiences have had with monologue-plays of the much praised young Irish playwright Conor McPherson, The Weir and The Lime Tree Bower (both currently playing in New York). As a folk singer accompanies himself with a guitar, the women at work in Michael Brown's dark, damp and dismal factory setting accompany the routine of examining and folding with chatter. This runs from bitching about the factory's increasing demand for greater speed in the face of declining business -- ("This is rotten work" declares Vera to which the quiet Rebecca wryly retorts, "It's work!" ) -- to talk about movies and movie stars, to badmouthing each other and frequently erupting into angry confrontations.

Though described as "funny" and indeed filled with humor, The Factory Girls could easily have been titled "Dead End" since it reflects the disappointments and dead ends in the lives glimpsed bit by bit. As shirts get folded and carted in and out of the examining room by Rosemary, (whom Gretchen Cleevely plays with a delicious mix of ditzyness and yearning), we see what makes each one tick. We also come to understand their desperate battle for the jobs they disdain.

While the play has a cast of seven, it belongs to the women. The two men (Malcolm Adams plays the union representative) are there but never really front and center. McHale as the manager, does have one brief and well-done scene when he asks the women to accept "voluntary redundancy".

For all its charm, fine acting and staging, The Factory Girls has its share of serious flaws. Topping the list is that understanding the thick Irish accents proves to be a considerable challenge for the audience. Kate Burton and Gretchen Cleevely most successfully project without sacrificing authenticity.

The second act though it has more dramatic tension than the first is nevertheless less satisfying. Much of this is a matter of misdirection and the loose ends typical of a first play. Even the set designer is slightly off the mark in putting an Apple computer in Bonner's office -- for even though these machines did exist at the time the play was written, a typewriter would have been more appropriate.

As the first section seems to want to end a scene before it actually does, so the shift in the strikers' willingness to persevere lacks transition. Ellen's festering guilt comes on too abruptly, as does the ending in general. This last is offset by Jeff Nellis' sensitive lighting which more than anything said gives the play a sense of hope that overrides the inevitable outcome of the sit-in. These "girls" may never get back their job, but their brief adventure has brought each of them the insight that will give them the courage to soldier on.

![]() The New

York Times

The New

York Times

Theater Review

Harry, A Man Of Many Parts

Thursday, June 11,1998

by Anita Gates

Pete, Bob and Mary walk into a bar. "You can't run around with primates

all your life" says Pete (Sean Weil), objecting to Mary's plan to adopt

an ape. Mary (Eva Patton) wants Pete and Bob (Lars Hanson) to be the ape's

co-godfathers. But the guys have other things on their minda. Pete recently

had a liver, kidney, panceas and partial-intestine transplant, so naturally,

he doesn't "have the guts anymore", as he explains, for his former

career as a journalist. Bob recently had a retina transplant and has given

up his career in seismology. Both men, however, admire Mary's new ears, which

she picked up recently at the Cornell Medical Center.

All this transplanting (and there's more) sets up the plot for "Harry

and the Cannibals", Susan Mosakowski's pleasant absurdist one-act play,

which continues at La Mama E.T.C through Sunday. Not to give too much away,

but the Harry of the title is deceased and he was an organ donor. The play's

bartender - waiter (Greig Sargeant) has an attitude problem, but so would

you if you'd been brought up by a father named Frank Stein (Raphael Nash Thompson)

and special ordered from the DuPont Institute of Eugenics.

This group of characters is soon joined by McCoy (Malcolm Adams, an actor

with an infectious Robert Downey Jr. demeanor), a former mortician who wants

to have sex with everyone, anyone, right now. They're all soon mesmerised

by a mysterious woman in black (Louise Favier) who has a film-noir presence

and a secret connection to Harry. Meanwhile, Baby (David Giambusso), Mary's

ape, has learned to talk but inexplicably speaks Spanish. His first word is

"leche". And Dr Lacuna (Frank Deal), who seems to be all the other

characters' favorite mental-health professional, sneaks moments alone with

his old heart, which he keeps in a jar. Yes, he's a recent transplant patient

too. Lacuna's leopard-skin psychiatrist's couch is one of several bright touches

in Paula Longendyke's clever stylish set.

Along the way to the predictable but cheerfully silly conclusion, Mr Adams

and Ms Favier capture a few moments of perfect absurdism. So does Mr Giambusso,

usually without speaking. The play's message - "We can't let go of anything;

we need all our parts", as McCoy says - seems appropriately pointless.